原文地址:https://flarkminator.com/2011/01/06/designing-enemies-bringing-it-home/

作者:Mike Birkhead(战神系列战斗系统高级设计师)

感谢作者和他的分享精神,我这里也不过是薪火传递,将好文引入国内。

到目前为止,我们的目标是分解和分析《Marvel vs Capcom 2》(MvC2)的战斗系统,但现在我们要转换方向。希望MvC2已经达到了它的目的,给了我们一些可用的想法。将这些想法应用于动作冒险游戏与为格斗游戏设计角色不同,就像为《GT赛车》设计汽车与为《火爆狂飙》设计汽车不同一样;不同风格的游戏有不同的设计目标。

格斗游戏的一个主要目标是尽量减少进入的障碍,并最大化心理战的潜力。这是通过最小化深度和最大化广度来实现的;我的意思并不是说一个角色不需要技巧来掌握,而是(在成功的游戏中)这种掌握可以适用于很多角色——我学会了龙拳,我也学会了虎膝。挑战在于判断和预测对手的动作,而不是执行自己的动作。

然而,动作冒险游戏有一个不同的目标:成就感。这需要玩家的深度和阵容的广度。玩家必须成长并有深度感,这不仅仅适用于他的攻击。玩家学到的每一个系统(魔法、攀爬墙壁、与世界互动)都是一个新的系统需要掌握,所以不要让玩家的攻击过于复杂。避免多余的攻击。这种“盒底设计”在引人入胜的游戏中没有立足之地。玩家不需要广度,因为他没有人可以进行心理战。他能骗谁呢?他只需要那些能以最酷的方式完成任务的动作。这也是为什么MvC2如此出色,因为游戏中的每个人物都在做各种疯狂而强大的动作。可以想象游戏设计师站在一个箱子上大喊:“狡猾是懦夫的!”我说阿门。

我们玩家的紧凑、专注和没有狡猾的设计也适用于我们的敌人。我们想要广度,但我们希望它来自整个角色阵容,而不是个别敌人。怪物不是来和玩家玩心理战的,它们是来让我感觉自己很厉害的。我想要粉碎它们的脸。如果我想要狡猾,我会玩格斗游戏。这种游戏是为心理战设计的,我会和真正的人玩,他们比电脑更难对付。这并不意味着你的敌人不能狡猾——他们可以而且应该有一个诡计。那是单一的诡计。玩家学会了怪物的诡计,一旦克服,就会有成就感。她变得比她的对手更强大了。

成就感是最好的动作冒险游戏的主要推动力,虽然你可能没有意识到这一点,但你知道当游戏未能带来这种感觉时。有时候你多次输给一个boss,挫败感逐渐增加,直到最后你靠运气赢了。这种经历很糟糕。最遗憾的是,这种糟糕的感觉更多是指向自己(为什么对我来说这么难?)而不是游戏(谁设计了这个垃圾)。

所以,如果你希望玩家感到成就感而不是问哪个白痴毁了他们的夜晚,有三件事需要记住。首先,你必须始终牢记你的角色阵容必须扮演的角色。其次,你必须以平衡的方式类型化你的角色阵容。第三,你必须找到你的诡计。

角色

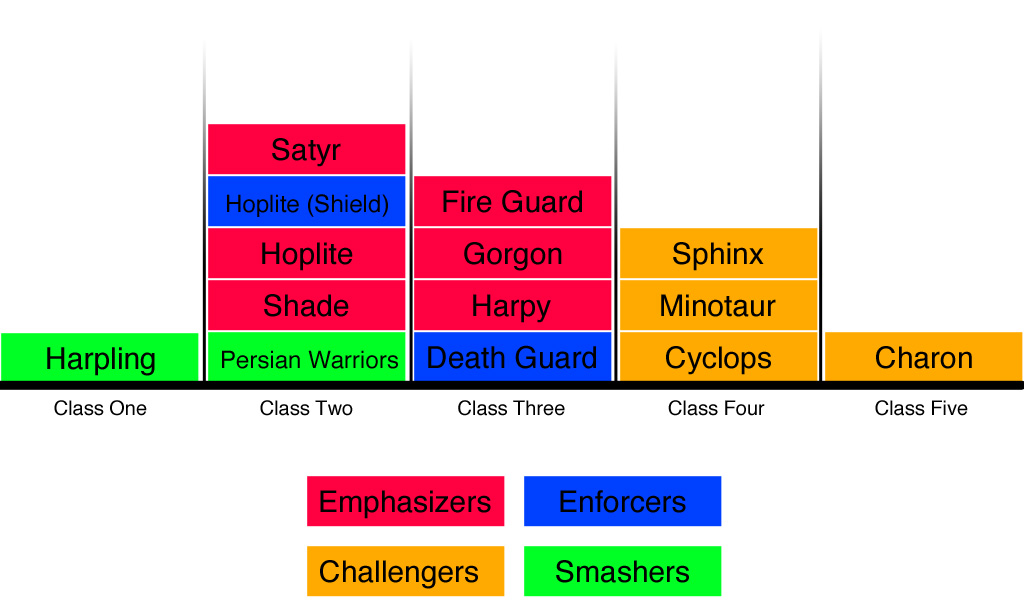

谈论角色时,具体细节是浪费的。你游戏的机制(每个游戏都是独特的)定义了敌人的角色。例如,在《战神》中,蛇发女妖的光束攻击通过使用Kratos的闪避来对抗,所以她的角色是强调闪避机制;这个角色在狭小空间或对抗需要承诺的重甲敌人时非常有吸引力。如果没有闪避机制,蛇发女妖就没有多大意义,这使她变得无聊和令人沮丧。我们必须从更高、更通用的层次来看待我们的角色阵容。这样做会形成一个独立于机制的四个主要重复角色的图景:强调者、强制者、粉碎者和挑战者。

强调者(Emphasizers)

在追求大众市场吸引力时,强调者应该占你角色阵容的大多数。如前所述,玩家有几种工具来应对她面对的生物。强调者是一种奖励而不是要求使用某种特定机制的生物。关键是要有积极的强化。你不会因为使用错误的方法而受到惩罚,只是因为以“正确”的方式做事而得到奖励。《战神》中有几个强调者的例子,但我特别喜欢蛇发女妖。

蛇发女妖被认为是一个高等级的生物,因为她不仅对玩家构成更大的挑战,还需要更多的工作来实现和创建。她很快,避开你的攻击,并且有她致命的凝视,如果玩家停留太久,会把Kratos变成石头。在幕后,当玩家“在”蛇发女妖的凝视锥形区域内时,游戏会启动一个计时器,如果计时器达到一定点,Kratos会变成石头;然而,如果玩家使用他的闪避(滚动),计时器会重置,无论Kratos是否仍在凝视中。闪避(滚动)在对抗这个生物时给玩家带来了优势,但Kratos并不需要这样做。例如,如果蛇发女妖用她的凝视攻击我,而我用一个足够重的攻击攻击她,她会停止凝视并对我的攻击做出反应。关键是“足够重的”攻击。并不是任何攻击都有效。只有Kratos最重的“终结”攻击才有效,但它仍然给玩家一个选择,而这个选择使她成为一个引人入胜的怪物。

假设我开始攻击一个生物,而蛇发女妖同时启动她的凝视攻击。我现在必须做出选择,是继续我的连击,希望我有时间用重攻击击中蛇发女妖(有风险),还是放弃我可能造成的伤害并滚开(安全)。这种有意义的选择来自于她强调机制而不是强制机制。很少情况下,敌人应该被构建为要求玩家采取特定行动。强调奖励实验,而要求则残酷地教导。前者自然流畅,随着时间的推移,玩家会发现最佳的行动方案。后者使游戏停滞不前,而玩家必须设计出正确的解决方案。有时你应该强制一种机制,而这些时候是你想要教玩家一些核心内容的时候。

强制者(Enforcers)

你的角色阵容的大多数应该是强调者,但它们也有缺点。通过允许多种击杀解决方案,它们缺乏强制教玩家的能力。有时你有一个机制是如此核心,以至于玩家必须学会它。进入强制者。这些生物要求玩家使用一种机制,如果玩家不使用它,他们将无法前进。

《战神》中的持盾敌人是强制者的完美例子。你不能抓住他们,你不能用轻攻击击中他们,唯一的方法是用“足够重的”攻击击破他们的盾牌。这些动作被称为他的“粉碎”动作,由Kratos连击的所有重结尾动作组成。(方块,方块,三角)——(方块,方块,方块,方块,方块,三角)。这些动作对《战神》的战斗是如此核心,以至于游戏希望确保玩家了解它们的力量。强制者有它们的位置,但它们的位置应该是罕见的。仅在必须教给玩家某些内容时使用,并尽可能明显地展示;这不是微妙的时候。微妙和强制者不太搭配,如果处理不当,很快会变得令人沮丧。

挑战者(Challengers)

这些是boss,难度较高的敌人,你需要使用工具箱中的所有工具来击败他们。挑战者与强调者和强制者分开,因为它们的设计复杂性和实现成本。大多数敌人可能只有一到两种攻击,而一个挑战者可能有三到四种攻击。记住,敌人的攻击越多,它们就越能与玩家玩心理战,而心理战是危险的。如果处理得当,捕捉玩家的意外并提供更大的挑战可以为游戏增添趣味,并推动玩家突破到新的掌握水平。然而,更多的时候,它们是令人沮丧的地狱,反复死于没有模式且不提供成就感的廉价战术。

我最喜欢的问题之一是问挑战和挫败之间的区别。虽然有不止一个答案,但我更喜欢简洁地定义:“挑战是与自己斗争,挫败是与游戏斗争。”挑战者,比任何其他敌人,都试图在挑战和挫败之间走那条细线。这些敌人通过插入难度峰值来控制游戏的流动,一个节奏良好的游戏遵循难度的正弦曲线。它从简单的任务开始,逐渐增加挑战,达到高潮,然后迅速缓解让你冷静下来。挑战者控制了我们节奏中的山峰,最后一组则构成了山谷。

粉碎者(Smashers)

为玩家提供挑战很重要,但有时你只想摧毁一些东西——很多东西。粉碎者是较小、较弱且容易被消灭的敌人,你可以单独投放,有时与其他敌人一起,让你尽情粉碎。记住,我们在这些游戏中的首要目标是给玩家一种成就感,而每隔一段时间让你的“大屠杀者”出来感觉真的很好。挑战者追求难度,而粉碎者追求简单。

注意:这种简单性不仅应适用于它们的难度,也应适用于它们的实现。粉碎者有一个次要功能。通过在AI、多边形数量、纹理大小和基本内存占用方面让它们轻量化,你可以在整个游戏中自由地散布这些敌人,而不会对关卡设计产生重大影响,当内存变得紧张时,我们都知道这有多重要。

两个组(强调者和强制者)通过玩家的机制定义。强调者,最常见的,奖励玩家使用特定机制而不是要求它,而强制者教玩家特定机制。剩下的组(粉碎者和挑战者)通过难度和实现来定义,这再次独立于具体机制。粉碎者是弱小且容易消灭的,而挑战者对玩家构成巨大挑战。这四个角色原型很重要,但如果我们想要一个在玩法风格上多样化的平衡角色阵容,它们还不够。为此,我们需要通过额外的标准对我们的生物进行分组。

类别

一个平衡的角色阵容在风格、复杂性和机制上是多样化的。在过去,这是一个简单而清晰的“瘦”、“中”、“胖”冰球运动员,但现在平衡有了更丰富的含义。在《战神》中,他们将敌人分为几类,这确保了讨论的清晰度,确保设计师(以及其他人)能够可视化他们的工作量,并确保游戏中有适当分布的变化。类别范围从包含所有轻量级烦人敌人的“害虫”到显然追踪boss的“boss”。

清晰而明确的类别对于有意义的讨论是必要的。为什么要花时间和精力描述一个怪物的存在,当你可以说他属于“害虫”类时,这样你们就有了一个共同的基础。要达到这种理解,需要你的设计部门既严格又一致。如果你懒惰、健忘或不一致,你会严重损害沟通。然而,奖励超过了危险,因为强制执行这点可以让其他部门不仅快速理解你想要什么,还可以理解它创造了多少工作(或者如果被砍掉会节省多少工作)。可视化你的工作量,在开始时很重要,但在结束时同样关键,当事情被砍掉时。你的砍掉需要节省时间,并且需要让游戏不留下游戏玩法中的空白。

类别还可以帮助你跟踪你的玩法变化。在MvC2中,你可以将所有角色分为三类:巨大(Sentinel)、快速(Spiderman)和远程(Cable)。巨大克制快速,快速克制远程,远程克制巨大——石头、剪刀、布。保持这三类的平衡可以维持平衡感,但假设我需要砍掉游戏中的三个角色。没有类别结构,我可能会无意中选择三个巨大组的角色,减少了快速角色的克制者,导致游戏感觉破碎和不平衡。

角色和类别,虽然看似重复,但为游戏服务于两个不同的目标。角色是关于玩家的,而类别是关于你的角色阵容的。玩家的机制需要与他配合良好的敌人,但仅通过这种特定镜头来看待你的角色阵容会导致你最终拥有很多功能上不同但视觉上相似的敌人。最终目标是一个多样化的角色阵容,而拥有类别有助于确保视觉多样性。

诡计

一切都必须有一个目的。如果你不能在两句话以内向我解释一个生物必须存在的原因,那么可以肯定玩家不会喜欢杀死它。缺乏目的会有效地将你的生物降级为非常华丽的可破坏物体。我认识的一位伟大设计师总是问:“这个家伙的诡计是什么?”这个问题一直伴随着我,这是一个很好的问题来问你的敌人。一个诡计意味着你可以愚弄我,但一旦我知道你的诡计,它就失去了效果。被愚弄会让你保持警觉,同时提供你学习和成长的机会,这导致了我们最终的成就目标。

所以我最后一次回到MvC2。如果有一个游戏可以被称为“诡计袋”,那就是这个游戏,但还有更多的诡计存在于其他游戏中,可以为你的无聊设计增添活力和生气。去吧,挖掘,研究他们所做的,如果你选择只带走一件事,那就是:想法是无意义的,执行才是一切。

你能想到的每一个动作都已经被某人创造出来了。挖掘他们的想法并不会让你成为一个糟糕的设计师,因为,不管你信不信,采取那个想法并将其执行到同样(如果不是更高的话)质量比你想象的要困难得多,如果你聪明,你会选择将所有有限的时间和逐渐减少的精力投入到最大限度的执行上。

Our goal until now has been the break down and analysis of MvC2′s combat system, but now we are going to switch gears. MvC2 has, hopefully, served its purpose and given us some usable ideas. Applying these ideas to an action adventure game is not like designing characters for a fighting game, just as designing cars for Gran Turismo is not like designing cars for Burnout; different styles of games have different design goals.

One of the major goals in a fighting game is to minimize your barriers to entry and maximize the potential for mind games. This is achieved through minimizing depth and maximizing breadth; by this I mean not that a character takes no skill to master, but that (in successful games) the mastery is applicable to numerous characters in the cast – I learn to Dragon Punch, I also learn to Tiger Knee. The challenge comes in judging and anticipating the moves of your opponent, not in executing your own.

Action adventure games, however, have a different goal: Accomplishment. This requires a depth of player and a breadth of cast. The player must grow and have a sense of depth, which applies to more than just his attacks. Every system the player learns (magic, climbing walls, world interactions) is a new system to master, so do not go crazy with the player’s attacks. Avoid superfluous attacks. This “back of the box” design has no place in compelling games. The player doesn’t need breadth, as he has no one to play mind games with. Who is he going to fool? He requires only the moves that get the job done, in the coolest way possible. Again, this is why MvC2 is so great, because everyone in that game is doing wacky, powerful shit all over the place. One can imagine the designers on that game standing on a box shouting, “Subtlety is for pussies!”, and I say Amen.

The tight, focused and subtlety-free design of our player also applies to our enemies. We want breadth, but we want it to come from the cast as a whole and not the individual enemies. The monsters are not there to play mind games with the player, they are there to make me feel like a bad ass. I want to smash faces. If I want subtlety, I will play a fighting game. A game which is DESIGNED for mind games, and I’ll play it with real people who are infinitely trickier than a computer. This does not mean that your enemies cannot be tricky – they can and should have a trick. That is trick, in the singular. The player learns the monster’s trick, and once overcome, gives her a sense of accomplishment. She is getting stronger and better than her adversaries.

Accomplishment is a major driving force behind the best Action Adventure games, and though you may not be consciously aware of it, you know when games have failed to grant that feeling. Have you ever lost to a boss numerous times in a row, your frustration growing to a boiling point, until finally you squeak out a victory more through luck than anything? I’ve been there, and it sucks. Most regrettable is that the shitty feeling is directed more to yourself (why was that so hard for me?) than the game (who designed this bullshit).

So if you want player’s feeling accomplished and not asking what idiot ruined their night, there are three things to keep in mind. First, you must always keep in the mind the roles your cast must fill. Second, you must type your cast in a balanced manner. Third, you must find your trick.

Roles

When discussing roles it is wasteful to speak in specifics. The mechanics of your game, which are unique to each game, define the roles for your enemies. In God of War, for example, the Gorgon’s beam attack is countered by using Kratos’s dodge, so her role is to emphasize the dodging mechanic; a role that makes her compelling in tight spaces or against heavily armored enemies that require commitment. With no dodge mechanic, the Gorgon serves little purpose, which leaves her boring and frustrating. We must instead instead view our cast from a higher, more generic level. Doing so forms a picture, independent of the mechanics, of four major reoccurring roles: Emphasizers, Enforcers, Smashers and Challengers.

Emphasizers

Emphasizers should, when striving for mass market appeal, make up the majority of your cast. As stated, your player has several tools in her toolbox for dispatching the creatures she faces. An emphasizer is a creature that rewards, not requires, the use of one specific mechanic. The key is to have positive reinforcement. You are not penalized for using the wrong method, simply rewarded for doing it the “correct” way. God of War has several examples of emphasizers, but I particularly like the Gorgon.

The Gorgon is considered a higher tier creature, in that she poses not only a greater challenge to the player but also requires more work to implement and create. She is fast, avoids your attacks, and has her deadly gaze, which if the player stays in too long, will turn Kratos to stone. Behind the scenes, when the player is “inside” the cone of the Gorgon’s gaze the game starts a timer, and if the timer ever reaches a certain point Kratos is turned to stone; however, if the player ever uses his dodge (roll) the timer is reset, regardless of whether Kratos is still in the gaze. Dodging (rolling) gives the player an advantage against this creature, but Kratos is not required to do this. For example, if the gorgon is hitting me with her gaze and I attack the gorgon with a significantly heavy enough attack she will stop her gaze and react to my attack. They key here is “significantly heavy enough” attack. Not just any attack will be effective. Only Kratos’s heaviest “ender” attacks work, but it still gives the player a choice and that choice is what makes her a compelling monster.

Let’s say I have started to attack a creature and at the same exact time the Gorgon has started up her Gaze attack. I must now make a choice, do I continue with my combo in the hope that I will have time to hit the Gorgon with my heavy attack (risky), or do I forgo the damage I could do and roll away (safe). This meaningful choice comes from her emphasizing mechanics and not enforcing mechanics. Very rarely, if ever, should enemies be constructed with the purpose of requiring a specific action from the player. Emphasis rewards experimentation, while requirements brutally teach. The former flows naturally, and over time the player discovers the best course of action. The latter brings the game to a screeching halt, while the player must deign the correct solution. There are times when you should enforce a mechanic, and those times are when you want to teach your player something core to the game.

Enforcers

The majority of your cast should be emphasizers, but they do have a downside. By allowing for multiple killing solutions they lack the ability to forcibly teach the player. Sometimes you have a mechanic that is so core to your design that a player must learn it. Enter the enforcers. These creatures require a mechanic from a player, and without the player using it, they will not progress.

The shield bearing enemies from God of War are the perfect example of Enforcers. You cannot grab them, you cannot hit them with light attacks, and the only way to get passed their shields is to hit them with a “significantly heavy enough” attack. These moves are known as his “crush” moves, and are made up of all the heavy ending moves of Kratos’s combos. (Square, Square, Triangle) — (Square, Square, Square, Square, Square, Triangle). These moves are so core to God of War combat that the game wants to make sure the player understands their power. Enforcers have their place, but their place should be rare. Use this only when something MUST be taught to the player, and do so with as much obvious flair as possible; this is not a time to be subtle. Subtly and enforcers do not mix well, and if handled poorly can quickly become frustrating.

Challengers

These are the bosses, the difficult enemies, the ones you use all of the tools in your toolbox to defeat. Challengers are separated from your emphasizers and enforcers due to their complexity of design and cost to implement. Where most enemies in your cast will have their one or at most two attacks, a challenger might have three or four. Remember, the more attacks you give an enemy the more it can play mind games with the player, and mind games are dangerous. Catching a player off guard and providing a greater challenge, if handled well, can spice up the game and drive the player to break through to a new level of mastery. More often, however, they are a hell of frustrating and repeated deaths to overly cheap tactics that follow no pattern and offer no accomplishment.

One of my favorite questions is to ask for the difference between challenging and frustrating. While there is more than one answer, I prefer to define it succinctly: “Challenging is a struggle against oneself, frustrating is a struggle against the game.” Challengers, more than any other, are the enemies that attempt to walk that fine line between challenging and frustrating. These enemies control the flow of your game by inserting spikes in the pacing, and a well paced game follows a sinusoidal curve of difficulty. It starts the player off with simple tasks, increases the challenge gradually up to a climax, and then quickly eases back to let you cool down. Where the challengers control the mountains of our pacing, the final group makes up the valleys.

Smashers

Providing the player with challenges is important, but sometimes you just want to destroy something – a lot of somethings. Smashers are the smaller, weaker and easily dispatched enemies that you throw at the player, sometimes alone, but most times accompanying other enemies, and they let you get your smash on. Remember our number one goal in these games is to give the player a sense of accomplishment, and letting your mass murderer out of the bag every once in a while feels really good. Where Challengers strive for difficulty, Smashers strive for simplicity.

Note: this simplicity should be applied not only to their difficulty, but also to their implementation. The Smashers serve a secondary function. By making them lightweight in terms of AI, poly count, texture size, and basic memory footprint, you can sprinkle these enemies liberally across the game, without having a major impact on your level designs, and we all know how important that is when memory becomes tight.

Two groups (Epmhasizers and Enforcers) are defined through the player’s mechanics. Emphasizers, the most common, reward the player for using a specific mechanic without requiring it, while enforcers teach a specific mechanic to the player. The remaining groups (Smashers and Challengers) are defined by difficulty and implementation, which again is independent of the specific mechanics. Smashers are weak and easily dispatched, while Challengers pose a great challenge to the player. These four role archetypes are important, but they are not enough if we want to have a balanced cast that is diverse in play style. For that we need to group our creatures by additional criteria.

Classes

A balanced cast is one diverse in style, complexity, and mechanic. In the old days, it was as simple and clean as a “skinny”, “medium”, and “fat” hockey player, but now balance has a more textured meaning. In God of War they break enemies down into several classes, which ensures clarity in discussion, ensures designers (and others) visualize their workload, and ensures there is a properly distributed variation in play. Classes range from “Pests” which contains all of the lightweight annoying enemies, all the way to “Bosses” which, obviously, tracks the bosses.

Clear and distinct classes are necessary for meaningful discussion. Why spend time and effort describing a monster’s presence when you could say he’s of class (to borrow the term) “Pests”, which starts you both on a mutual foundation. To reach this understanding requires your design department be both vigorous and consistent. If you are lazy, forgetful or inconsistent, you will seriously harm communication. The rewards, however, outweigh the dangers, as enforcing this lets other departments quickly understand not only what you want, but also how much work it creates (or saves if it’s cut). Visualizing your workload, while important in the beginning, is just as critical near the end when things are being cut. Your cuts need to save time and they need to leave the game without a gap in its play.

Classes can also help you to keep track of your play variation. In MvC2 you can break all characters down into three classes: Huge (Sentinel), Quick (Spiderman), and Ranged (Cable). Huge counters quick, which counters ranged, which counters huge – rock, paper, scissors. Keeping these three classes even maintains a feeling of balance, but say I need to cut three characters out of the game. Without class structure, I could unknowingly choose three characters out of the Huge group, and with fewer counters to the quick characters, leave the game feeling broken and unbalanced.

Roles and Classes, while appearing redundant, serve two distinct goals for the game. Roles are about the the player, while Classes are about your cast. The mechanics of your player demands enemies that work well against and with him, but only viewing your cast through that particular lens leads you to end up with lots of functionally distinct but visually similar enemies. The ultimate goal is a diverse cast, and having Classes helps to ensure visual diversity.

Tricks

Everything must serve a purpose. If you cannot explain to me why a creature must exist – in less than two sentences – then it’s a safe bet the player is not going to enjoy killing it. Lacking purpose reduces your creatures, effectively, into very fancy desctrucible objects. A great designer I know always asks, “What’s this guy’s trick?” The question has stuck with me, and it’s a great question to ask of your enemies. A trick implies that you can fool me, but once I know your trick it loses its effectiveness. Being fooled keeps you on your toes, while providing you with the opportunity to learn and grow as a player, which leads to our ultimate goal of accomplishment.

And so I return, one last time, to MvC2. If ever there was a game that could be called a Bag of Tricks, it is this game, but there are even more tricks out there, existing in other games, that can add spice and vitality to your boring designs. Go, mine, study what they have done, and if you choose to take away only one thing, let it be this: ideas are meaningless, execution is everything.

Every move you can think of has already been created by someone. Mining their ideas doesn’t make you a bad designer, because, believe it or not, taking that idea and executing it to the same (if not higher) quality is harder than you can ever imagine, and if you are smart, you will choose to devote all your limited time and dwindling energy on executing to the fullest of your extent.